Even die-hard fight freak Charles Dickens would agree:

Last week was the best of weeks. And it was the worst of weeks.

The former tag applies largely because of a Saturday night spent flitting between Las Vegas and central California, where dueling cards produced by Showtime and ESPN yielded compelling and street cred-enhancing main events at 168 and 140 pounds – alongside a bona fide prospect-legitimizer at 154, a dubious decision at 135 and a women’s world-title unifier/star-maker at 105.

For those who were tuned in to basketball, here are a few quick takeaways. David Benavidez is a beast. Jose Ramirez is a stud. Jesus Ramos is a problem. And Seniesa Estrada is a phenom.

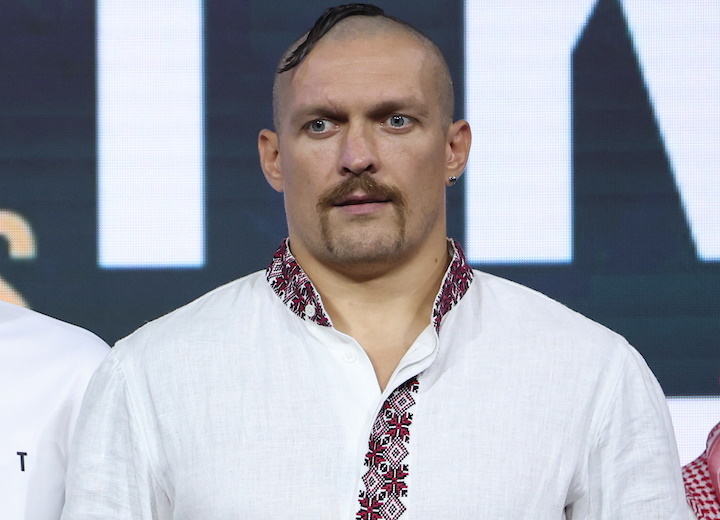

And as for the latter tag… see any Google-searched story including the names Fury and Usyk.

Their back-and-forth blather was not only petty and juvenile, but it also cost fans – and the sport as a whole – a shot at the kind of mainstream legitimacy that having one heavyweight champion can bring.

It’s a fitting sequel to a similar tale penned just a few months earlier at welterweight, where would-be foes Terence Crawford and Errol Spence Jr. managed to bicker themselves out of a generational showdown that may have put them in the discussion for a spot on the 147-pound Mount Rushmore.

And c’mon, who’d really be surprised if Canelo and Benavidez never fight? This year or ever.

Because boxing.

But rest easy, you stubborn types. It’s not having a real impact.

Beyond continuing to marginalize boxing while clearing room for other sports to be great, that is.

Oh sure, the “love it or leave” types will point to huge crowds at Wembley or Abu Dhabi as ample evidence the sport is as healthy as ever, while calling out dissenters as disloyal to the cause.

But what they may fail to mention is that each time a Fury-Usyk or a Spence-Crawford falls flat at the negotiating table – just a few less people care the next time a subsequent big event is rumored.

Why bother getting excited, they’ll suggest. It’ll never actually happen.

And as often as not in this era, they’re right.

Don’t think so? Look back 20 or so years and realize how the landscape has changed.

Ironically, running alongside the early portions of Saturday’s dueling ring cards was a weekly UFC Fight Night show from San Antonio that was available on basic cable.

Among its 10 bouts were no fewer than three that matched pairs of ranked contenders in their given weight classes, including a former champ in the co-main and an ex-title challenger in the main.

Did it have the single-fight star power of Benavidez and Plant? No.

Given that it was “free” on ESPN and not $74.99 via pay-per-view, it wasn’t such a bad option, though.

And if you’re a casual fan looking for something to watch on a whim, guess where you’re going.

But that’s not the only contrast to be drawn from the week just passed.

As boxing’s perpetual self-inflicted wounds – gaggles of champions and aborted mega-fights, among them – have slowly reduced it to punch-line status with mainstream sports consumers, you needn’t search far for the combat option that’s been elevated to household status as the ring empire crumbled.

Can Dana White be a bald-faced jackass? Yes.

But regardless of your vibe about the UFC czar’s political allegiances, his domestic indignities or the repugnant nonsense being marketed as “Power Slap,” it’s impossible to deny his business sense.

By pulling all aspects of the fight-making process – athlete contracts, matchmaking, promoting, rankings, etc. – under one centralized umbrella, White has built himself a competitive colossus whose footprint expands with each sold-out arena and every numbered pay-per-view show.

Why, you ask?

Because, unlike modern boxing, when there’s a hotshot champion and a high-profile contender, they don’t quibble about promoters, haggle about streaming services or wrangle about site selections.

More often than not, it’s pretty simple. They fight.

And people watch. Warts and all.

Do the high-enders make as much in the tightly-controlled framework as they could in the free enterprise zone maximized by the likes Floyd Mayweather Jr.? No. But if you judge the health of a sport by the zeal of its fanbase and not the Ferraris owned by its upper crust, the scorecards seem clear.

Where boxing has promotional fiefdoms loathe to cede turf even at the expense of the greater good, the UFC has a singular authoritarian purpose – to stifle opposition by any means necessary.

Wondering if it’s working?

Swing by your local sports bar on a Saturday night and see what’s playing on the main screens.

Autocracy in action.

“Dana was intelligently able – with the help and vision of Ari Emanuel – to bypass a lot of the entrepreneurial business challenges that so bedevil boxing and instead pursue the greater efficiency and control a dictatorship afforded him,” ex-HBO mic man Jim Lampley told BoxingScene. “And along with it to control the narrative and maximize the output of his competition for impact in the marketplace.

“Imagine for instance what could have happened in boxing if Top Rank with its superior matchmakers and history had been able to do business with no functional competition and no governing bodies to restrict them. That is what Dana had.”

* * * * * * * * * *

This week’s title-fight schedule:

Vacant WBO featherweight title – Tulsa, Oklahoma

Isaac Dogboe (No. 1 WBO/No. 9 IWBR) vs. Robeisy Ramirez (No. 2 WBO/Unranked IWBR)

Dogboe (24-2, 15 KO): Fifth title fight (2-2); Held WBO title at 122 pounds (2018, one defense)

Ramirez (11-1, 7 KO): First title fight; Fighting in sixth U.S. state (PA, CA, FL, NV, NY)

Fitzbitz says: Ramirez lost some luster when he flubbed his debut but he’s exactly the sort of fighter who should handle a fighter of Dogboe’s ilk. He gets a belt and sets up his future. Ramirez in 10 (99/5)

Last week’s picks: 1-0 (WIN: Okolie)

2023 picks record: 7-2 (77.8 percent)

Overall picks record: 1,257-410 (75.4 percent)

NOTE: Fights previewed are only those involving a sanctioning body’s full-fledged title-holder – no interim, diamond, silver, etc. Fights for WBA “world championships” are only included if no “super champion” exists in the weight class.

Lyle Fitzsimmons has covered professional boxing since 1995 and written a weekly column for Boxing Scene since 2008. He is a full voting member of the Boxing Writers Association of America. Reach him at fitzbitz@msn.com or follow him on Twitter – @fitzbitz.

Leave a Reply