As everyone grows up, our education grows with us. The details and rigors deepen in parallel to the inches we add. Elementary history books, as one example, start short on words and long on pictures. It doesn’t stay that way for long.

Perhaps the easiest symbol of the connection between growing bodies and growing minds is the ever expanding size of the textbooks we carry along for the ride. Those who continue their education into college and beyond can remember their textbooks well. They cost more, weigh more, and have more to say with each new degree of difficulty. The best of them don’t get sold back to the campus bookstore at the end of the semester. They remain of the shelf forever, a valuable reminder of the value they added not just to studies but to the life that comes with them

There are many great boxing books and biographies.

In 2006, SL Compton produced one that comes closer than almost any other to the experience of a treasured textbook. With the heft of a door stop, Compton tells the story of the great Harry Greb in staggering detail. Researched over more than a decade, Compton’s Live Fast, Die Young: The Life and Times of Harry Greb spells out, over the course of more than 600 pages, why the legend of the Pittsburgh Windmill endures to this day.

Earlier in this series, reviewing Springs Toledo’s more concise examination of Greb’s 1919 45-fight unbeaten campaign as an intended bookend with this tome, it was noted:

In a time when being in the ring often was how food made the table for many a battler, it’s logical to think fighting hard enough to entertain yet controlled enough to insure continued availability, while local papers often gave their opinion of verdicts to satisfy the gambling lines, might not always make for the most reliable results. Toledo captures why Greb stands out as a contest to such logic. Accounts of Greb captured in Smokestack Lightning don’t depict a fighter moving at anything but full speed.

Compton’s breadth of detail takes it a step further. With lengthy first hand accounts drawn from multiple sources, for fight after fight in an almost 300 fight career, Compton paints an exhaustive picture of the career of Greb from its beginnings to its tragic end. It’s impossible to read through the events of Greb’s career and not come away a little bit in awe. As a resume on paper, Greb’s is fantastic. Given full body by Compton, it’s something more audacious.

Compton creates a fascinating read on multiple levels. The first comes via its value in fleshing out a career that, to date, hasn’t surfaced film. For those who keep the flame burning in hopes we will one day see more than training clips of Greb, there are multiple accounts that should keep fingers crossed.

Greb was filmed, multiple times, and those films were shown to the masses. Sadly, likely none of those masses remain. Somewhere, sometime, in some random attic or cedar chest, there may yet be a few moments left to observe what Greb looked like in action. It hasn’t happened yet. Compton’s telling of the saga of Greb is as good an argument against film being a final decider as one can find.

On another level, the book works as a time capsule for a sport that doesn’t really exist anymore. Yes, there is still professional boxing and readers will see similarities. The description of the efforts of manager James Mason to goad opponents into the ring and work the press is a clear relation to the social media galvanization efforts of today.

But the idea of barnstorming from town to town, booking multiple engagements only days apart, chasing title opportunities that could take years to materialize while the body collected rounds by the hundreds. Greb endured broken bones, painful infections, accidents, efforts to win over the valuable New York press, and personal tragedies with rarely more than a month or two between engagements. There were early losses as he honed his craft and we see the idea of a fighter having to grow past the likes of George Chip or Tommy Gibbons. By the time Greb toppled Johnny Wilson for the middleweight title in 1923, Greb may already have been the best fighter of his age for more than four years.

There was no WBA sub-title around to win in the waiting (though there was an American version of the light heavyweight crown).

The book also serves as a fun mythbuster in spots. The legend of the post-fight bar scrap with Mickey Walker is dispelled, though it’s vibrancy and endurance makes it ultimately unkillable. Greb may have enjoyed late nights but his partying reputation comes off as overstated.

Compton makes a strong case against the reputation of Greb as a dirty fighter. He doesn’t do it by making the case that he never engaged in crafty tactics. Instead, Compton illustrates a line in Greb’s career, a before and after picture, centered around his first battle in 1921 with Kid Norfolk. That was the fight where Greb lost sight in his right eye and the accounts of Greb’s fights shift from that moment.

Astoundingly, Greb had already beaten a slew of the best middleweights, light heavyweights, and even heavyweight of his time with two good eyes. All of that was before Gene Tunney, before Tommy Loughran, and before Walker.

The Tunney rivalry gets a particularly deep dive. Officially, Greb beat Tunney only once. Compton’s research makes clear there should have been more and leaves an argument that Tunney may not have truly defeated Greb until their fifth and final meeting. Also well detailed are Greb’s Wile E. Coyote-like efforts to secure a shot at Jack Dempsey. If Dempsy ducked Greb, and the evidence is strong in that regard, he had company in several middleweight and light heavyweight champions over the years.

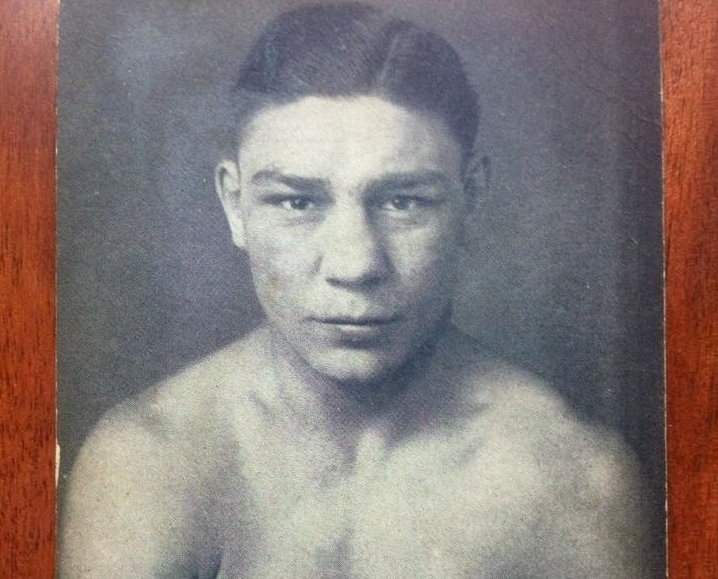

Accompanying the text is an impressive collection of photographs, personal and professional, that help to set the reader in the times described. They don’t just bring Greb to life; they bring opponents, locations, and some of the fights themselves into focus in a way few other boxing books do for any subject.

A great textbook leaves a willing student with a new regard for the subject at hand and an acquired piece of genuine wisdom. What Compton accomplished with Greb is a textbook for the ages. It is highly recommended and available on Amazon for anyone willing to invest the time.

It will be time well spent.

While the sport is largely postponed, boxing has a rich library of classic fights, films, and books to pass the time. In terms of fights, readers are welcome to get involved. Feel free to email, comment in the forum, or tweet @roldboxing with classic title fight suggestions. If they are widely available on YouTube, and this scribe has never seen them or simply wants to see them again, the suggestion will be credited while the fight is reviewed in a future chapter of Boxing Without Boxing.

Previous Installments of Boxing Without Boxing

Smokestack Lightning – Harry Greb, 1919

Roger Mayweather Vs. Serrano/Arredondo

Ruben Olivares-Zensuke Utagawa

Eddie Mustafa Muhamad vs. Michael Spinks

Michael Carbajal-Muangchai Kittikasem

Roberto Duran vs. Iran Barkley

Hedgemon Lewis vs. Carlos Palomino

Manuel Ortiz vs. Luis Castillo III

Chan-Hee Park vs. Guty Espadas

Simon Brown vs. Terry Norris I

Cliff Rold is the Managing Editor of BoxingScene, a founding member of the Transnational Boxing Rankings Board, and a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America. He can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply